|

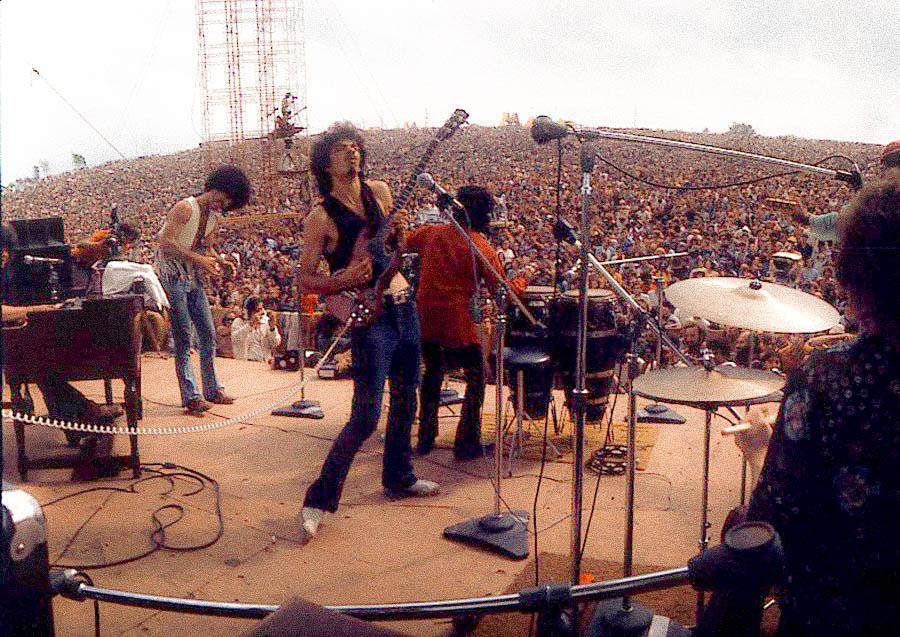

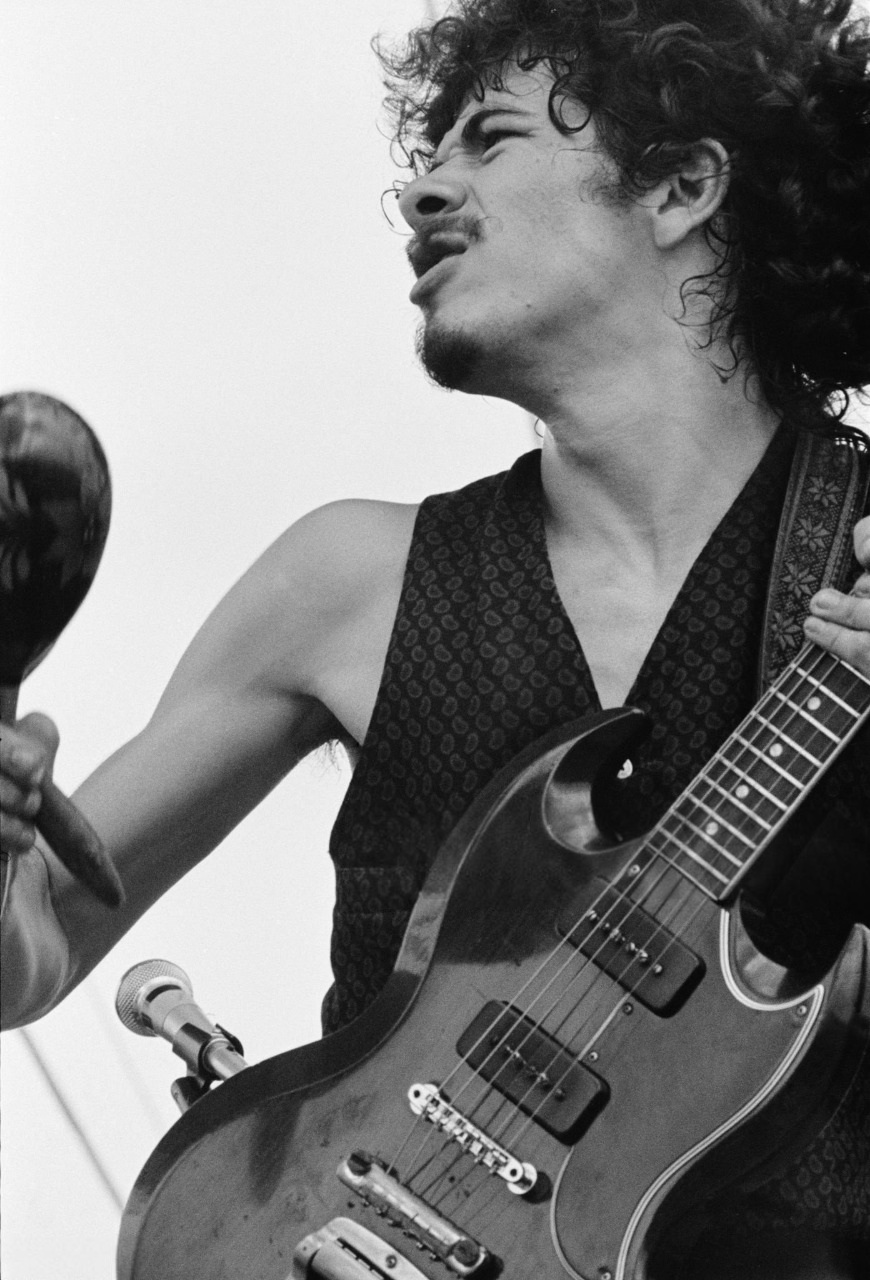

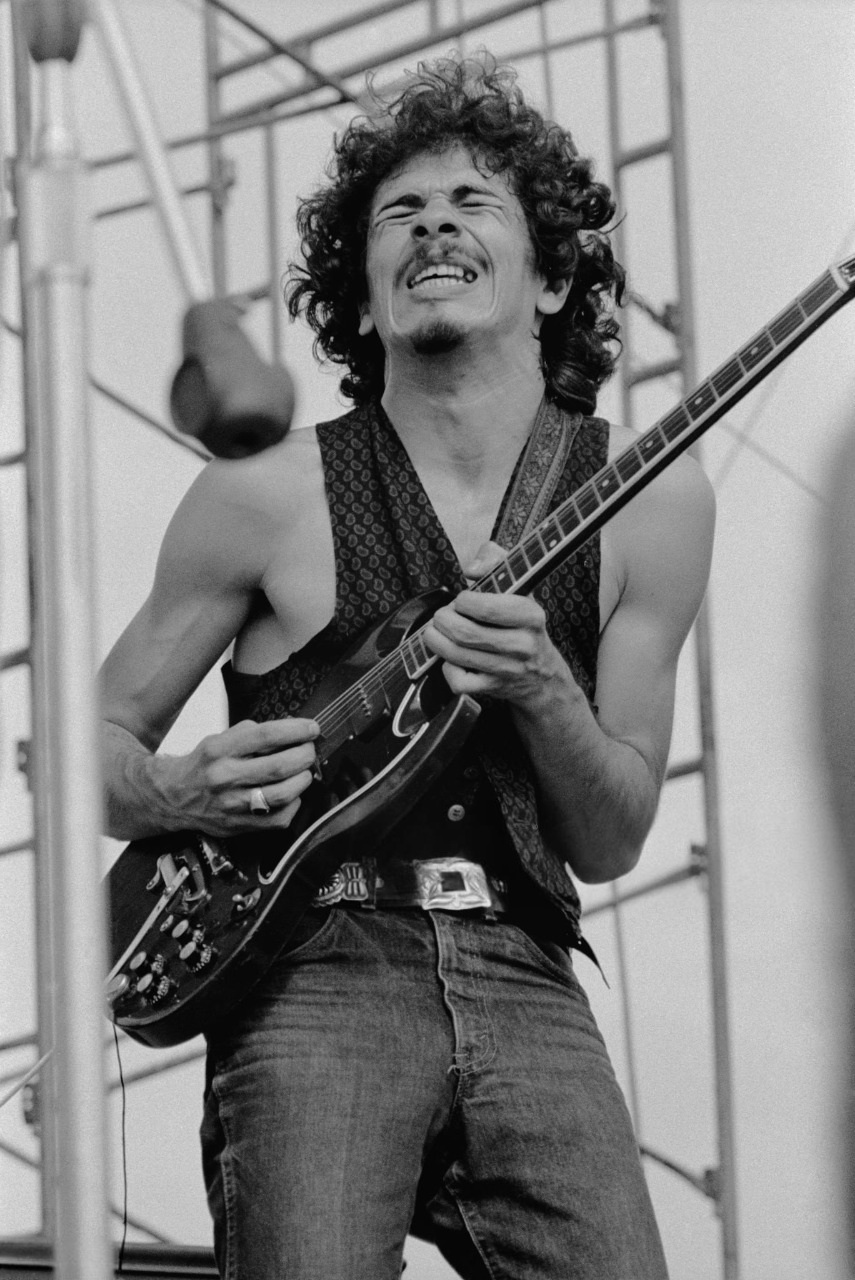

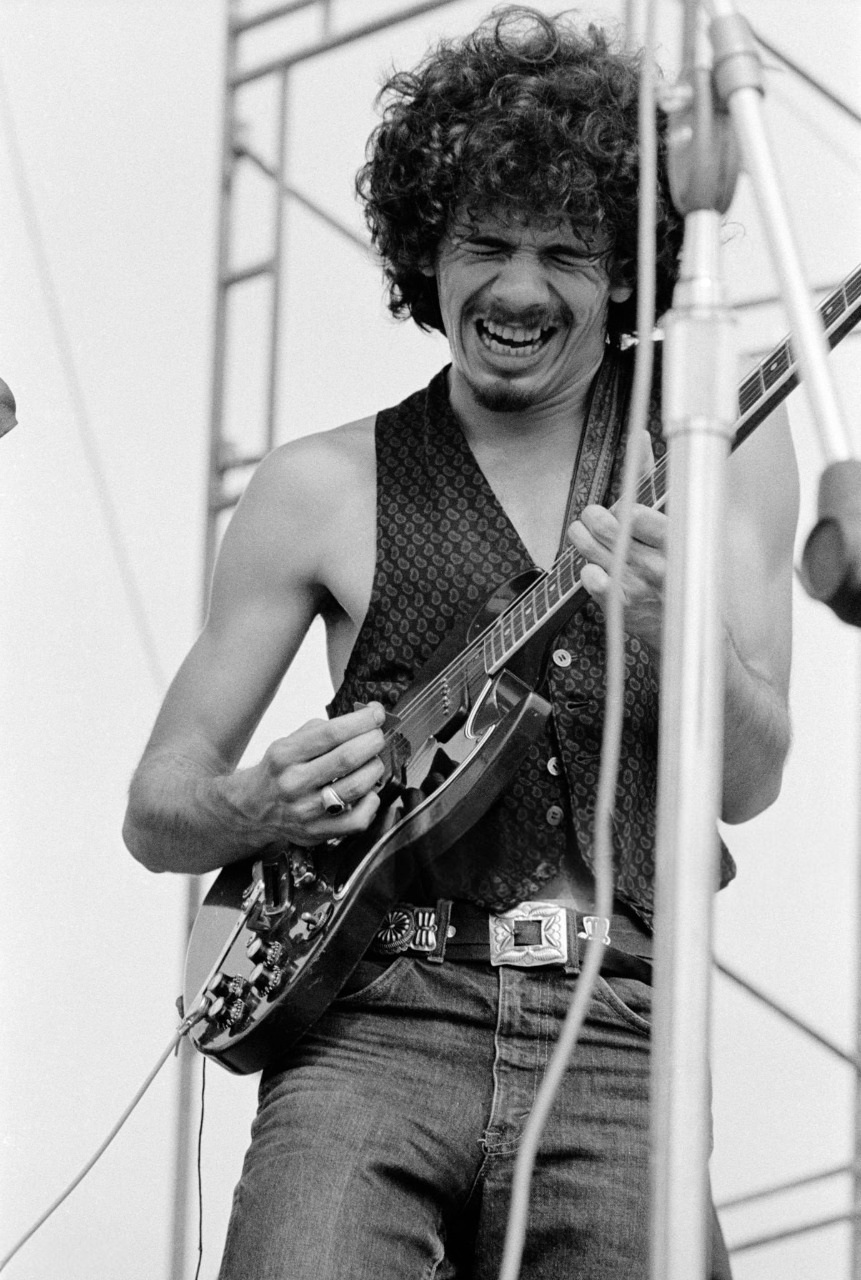

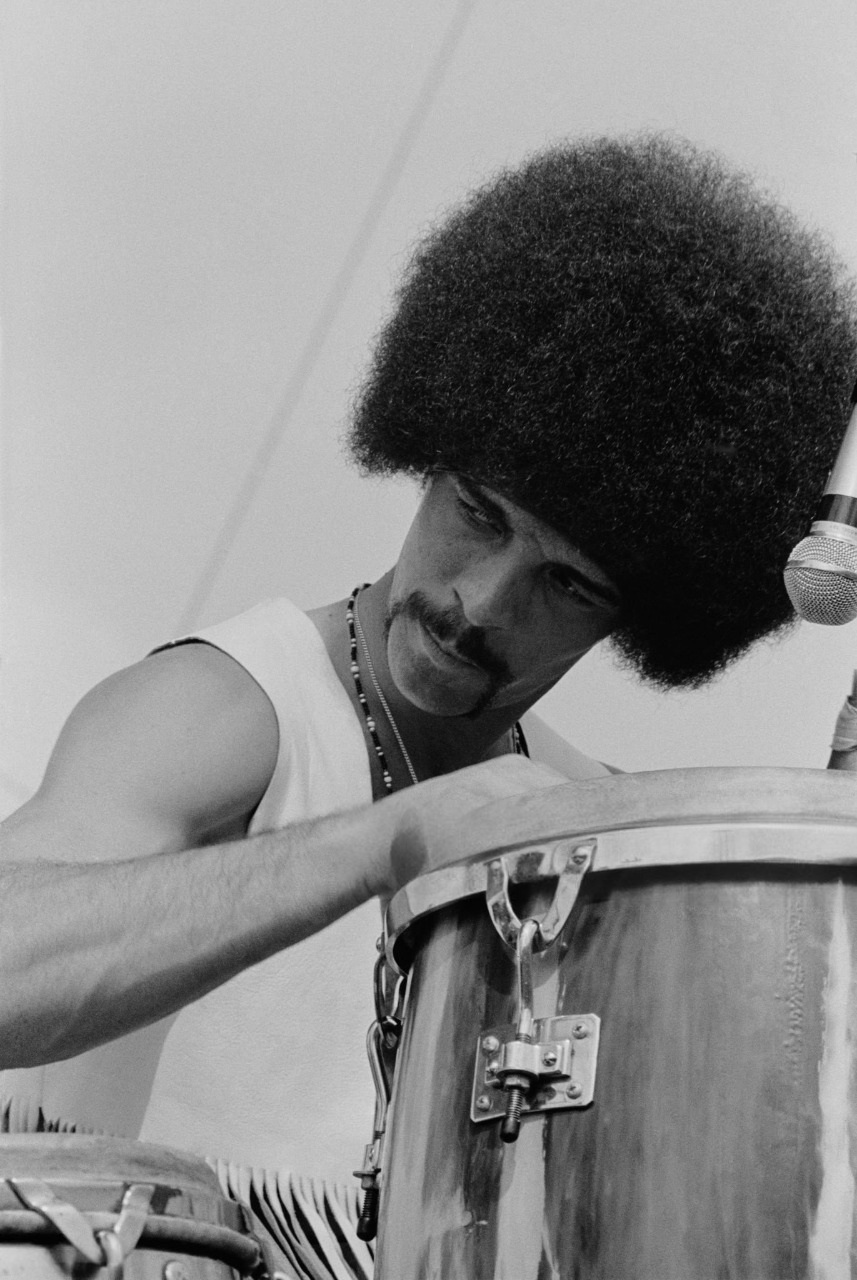

The Venue Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to simply as Woodstock, was a music festival held August 15-18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, 40 miles (65 km) southwest of the town of Woodstock. Billed as "an Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music" and alternatively referred to as the Woodstock Rock Festival, it attracted an audience of more than 400,000. Thirty-two acts performed outdoors despite sporadic rain. The festival has become widely regarded as a pivotal moment in popular music history as well as a defining event for the counterculture generation. The event's significance was reinforced by a 1970 documentary film, an accompanying soundtrack album, and a song written by Joni Mitchell that became a major hit for both Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Matthews Southern Comfort. Music events bearing the Woodstock name were planned for anniversaries, which included the tenth, twentieth, twenty-fifth, thirtieth, fortieth, and fiftieth. In 2004, Rolling Stone magazine listed it as number 19 of the 50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock and Roll. In 2017, the festival site became listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Woodstock was initiated through the efforts of Michael Lang, Artie Kornfeld, Joel Rosenman, and John P. Roberts. Roberts and Rosenman financed the project. Lang had some experience as a promoter, having co-organized the Miami Pop Festival on the East Coast the prior year, where an estimated 25,000 people attended the two-day event. The original venue plan was for the festival to take place in the town of Woodstock itself, possibly near the proposed recording studio site owned by Alexander Tapooz. After local residents quickly rejected that idea, Lang and Kornfeld thought they had found another possible location at the Winston Farm in Saugerties, New York. But they had misunderstood, as the landowner's attorney made clear, in a brief meeting with Roberts and Rosenman. Growing alarmed at the lack of progress, Roberts and Rosenman took over the search for a venue, and discovered the 300-acre (1.2 km2) Mills Industrial Park in the town of Wallkill, New York, which Woodstock Ventures leased for $10,000 in the Spring of 1969. Town officials were assured that no more than 50,000 would attend. Town residents immediately opposed the project. In early July, the Town Board passed a law requiring a permit for any gathering over 5,000 people. The conditions upon which a permit would be issued made it impossible for the promoters to continue construction at the Wallkill site. Reports of the ban, however, turned out to be a publicity bonanza for the festival. In his 2007 book "Taking Woodstock", Elliot Tiber relates that he offered to host the event on his 15-acre (61,000 m2) motel grounds, and had a permit for such an event. He claims to have introduced the promoters to dairy farmer Max Yasgur. Lang, however, disputes Tiber's account and says that Tiber introduced him to a realtor, who drove him to Yasgur's farm without Tiber. Sam Yasgur, Max's son, agrees with Lang's account. Yasgur's land formed a natural bowl sloping down to Filippini Pond on the land's north side. The stage would be set up at the bottom of the hill with Filippini Pond forming a backdrop. The pond would become a popular skinny dipping destination. Filippini was the only landowner who refused to sign a lease for the use of his property. The organizers once again told Bethel authorities they expected no more than 50,000 people. Despite resident opposition and signs proclaiming, "Buy No Milk. Stop Max's Hippy Music Festival", Bethel Town Attorney Frederick W. V. Schadt, building inspector Donald Clark and Town Supervisor Daniel Amatucci approved the festival permits. Nonetheless, the Bethel Town Board refused to issue the permits formally. Clark was ordered to post stop-work orders. Rosenman recalls meeting Don Clark and discussing with him how unethical it was for him to withhold permits which had already been authorized, and which he had in his pocket. At the end of the meeting, Inspector Clark gave him the permits. The Stop Work Order was lifted, and the festival could proceed pending backing by the Department of Health and Agriculture, and removal of all structures by September 1, 1969. The late change in venue did not give the festival organizers enough time to prepare. At a meeting three days before the event, Rosenman was asked by the construction foremen to choose between (a) completing the fencing and ticket booths (without which Roberts and Rosenman would be facing almost certain bankruptcy after the festival) or (b) trying to complete the stage (without which it would be a weekend of half a million concert-goers with no concert to hold their attention.) The next morning, on Wednesday, it became clear that option (a) had disappeared. Overnight, 50,000 "early birds" had arrived and had planted themselves in front of the half-finished stage. For the rest of the weekend, concert-goers simply walked onto the site, with or without tickets. Though the festival left Roberts and Rosenman close to financial ruin, their ownership of the film and recording rights turned their finances around when the Academy Award-winning documentary film Woodstock was released in March 1970. Santana performed on Saturday August 16, 1969 from 2:00 p.m. to 2:45 p.m. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

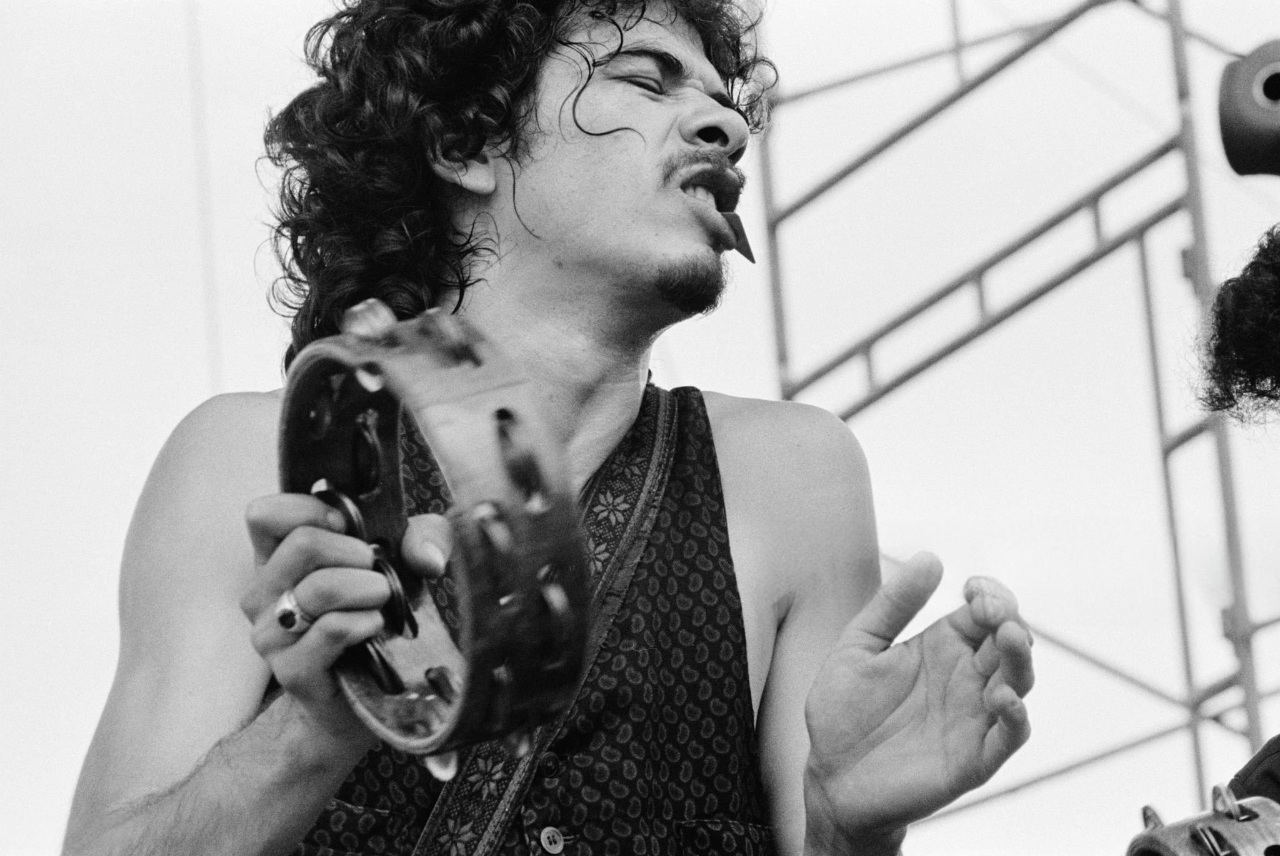

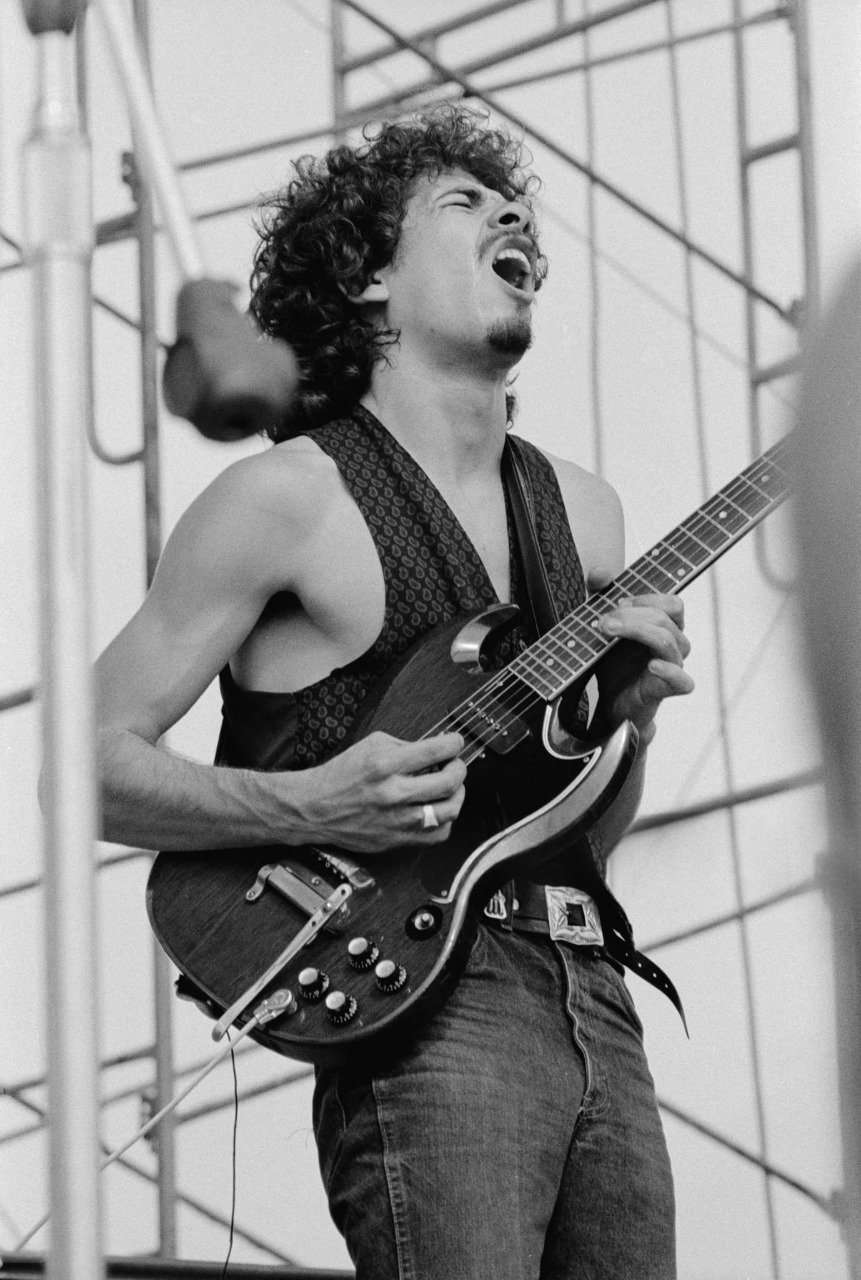

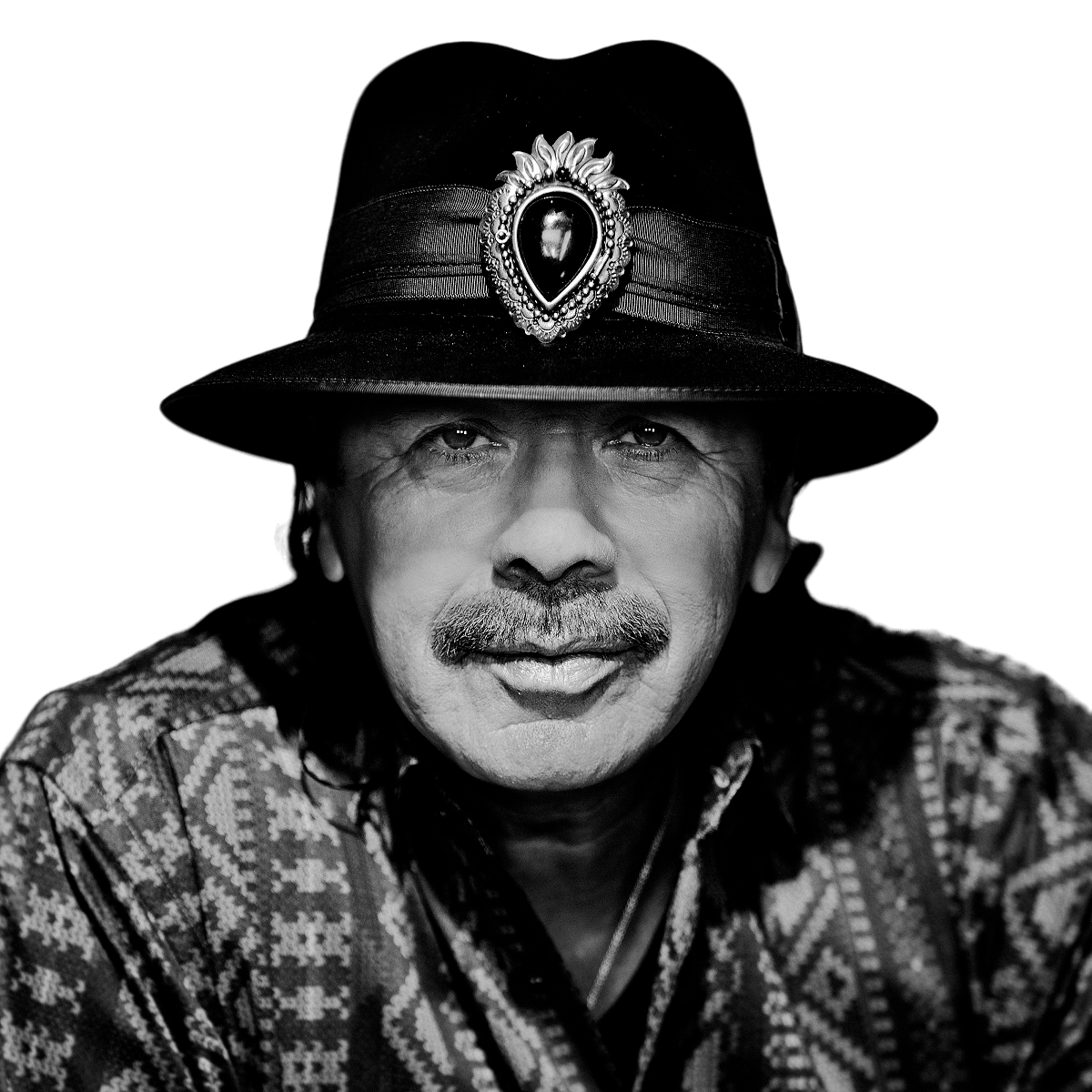

Woodstock Remembered: Carlos Santana on the Spiritual Vibe of the Fest. Rolling Stone August 5, 2019 It was a bit scary to go out there and plug into this ocean of hair, teeth, eyes, and arms. It was incredible. I’ll never forget the way the music sounded bouncing up against a field of bodies. You never forget that sound. For the band as a whole, it was great. But I was struggling to keep myself grounded, because I had taken some strong psychedelics right before I went onstage. When we first got there, around 11 in the morning, they told us that we weren’t going on until 8 o’clock. So I said, “Hey, I think I’ll take some psychedelics, and by the time I’m coming down, it’ll be time to go onstage and I’ll feel fine.” But when I was peaking around 2 o’clock, somebody said, “If you don’t go on right now, you’re not gonna go on.” We stuck around that whole evening, and I got to witness the peak of the festival, which was Sly Stone. I don’t think he ever played that good again — steam was literally coming out of his Afro. Musically, though, Altamont was better than Woodstock. I’m sorry people got hurt, but I have to say that everybody played incredible at Altamont: the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane, ourselves. Woodstock had more of a spiritual vibe; it was more of a spiritual celebration. Woodstock signified the coming together of all the tribes. It became apparent that there was a lot of people who didn’t want to go to Vietnam, who didn’t see eye to eye with Nixon and none of that system, you know? The people who started that movement in Haight-Ashbury taught me the difference between deals and ideals, between artists and con artists. They were not phonies, like the people wearing wigs in those commercials advertising old Sixties hits. The real people were wonderful. You could see American Indians and white people in love with life. Woodstock was a part of that. It was the same movement that got people out of Vietnam and got Nixon out of power. Some people called it a disaster area, but I didn’t see nobody in a state of disaster. I saw a lot of people coming together, sharing and having a great time. If that was out of control, then America needs to lose control at least once a week. Maybe I’m too naive, but I still see it like that. I saw a lot of positive, artistic, creative stimuli for America. In the Sixties, people didn’t go to concerts to get drunk and pick up chicks; they went to get bombarded with music and be taken somewhere else. When you came out, you knew you were never gonna be the same. You didn’t go to a concert to escape. You went to a concert to expand. A lot of the con artists in America have turned rock music into a kind of Gap-McDonald’s corporation music. You hear the same crap in every shopping mall. Everything is like Campbell’s soup instead of real gumbo, you know? We need more Jimi Hendrixes and Jim Morrisons. We need more rebels and renegades. As for the movie, I don’t like the fisheye lens that made me look like a bug, but all in all I’m very grateful. I keep telling my wife that we’re very blessed because we have a whole pocketful of memories and a video to back it up. Basically, I’m very grateful I got the opportunity to play at Woodstock. I could still be in Tijuana, across the border with no papers. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Memorabilia |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Film Release Ads |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

The Band: Santana #5 Carlos Santana (guitar/percussion/vocals), David Brown (bass), Michael Shrieve (drums), Michael Carabello (percussion), Jose “Chepito” Areas (percussion), Gregg Rolie (keyboard/vocals) Exact Set List Waiting (1) - Evil Ways (2) - You Just Don't Care (3) - Savor (4) - Jingo (5) - Persuasion (6) - Soul Sacrifice (7) - Fried Neckbones And Some Home Fries (8) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 1970 on 3LP (gf) (Atlantic/Cotillion USA/Germany SD 3-500) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in July 1970 on 3LP (gf) (Atlantic Japan MT 9065/7) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in April 1971 on 3LP (gf) (Atlantic Japan P-5003•4•5A) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 1980 on Warner Pioneer 10th Year Wea-Way '80 Hot Rod 3LP (gf) (Atlantic Japan P–4616~8A) (7) "Woodstock" in 1985 on Limited Edition Original Master Recording 5LP (box set/remastered) (Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab USA MFSL 5-200) (7) "Woodstock" on July 9, 2019 on Limited Edition Summer Of ’69 3LP (blue & pink vinyl) (Cotillion Worldwide RCV1 518805) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 2020 on 3LP (Cotillion Europe R1 518805) (7) "Woodstock" in 1985 on Numbered Limited Edition Original Master Recording 4CD (slipcase/remastered) (Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab USA MFCD 4-816) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" on May 25, 1987 on 2CD (Atlantic Japan 55XD-626/7) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" on August 10, 1989 on Forever Young Series 2CD (Atlantic Japan 32P2-2893~4) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 1989 on Special Edition 2CD + VHS-PAL (box set/numbered) (Atlantic Germany 780294-2) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 1994 on The 25th Anniversary 2CD (remastered) (Atlantic Japan 32P2-2893/4) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 1999 on 2CD (remastered) (Atlantic Germany 7567-90305-2) (6)(7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" in 2008 on 3CD (Cotillion/Rhino Records USA R2 518805) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" on June 2, 2009 on 40th Anniversary 2CD (remastered) (Cotillion/Rhino Records Europe 8122-79872-8) (7) "Woodstock. Music From The Original Soundtrack And More" on July 8, 2009 on 2CD (remastered) (Cotillion Japan WPCR 13541~2) (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8) "Santana. The Woodstock Experience" on June 30, 2009 on Limited Edition 2CD (numbered) (Sony/Legacy USA/Europe 88697 48242 2) (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8) "Santana. The Woodstock Experience" on July 22, 2009 on Limited Edition 2CD (Sony Records Int'l Japan SICP 2318~9) (4)(7)(8) "Santana" on March 31, 1998 on 30th Anniversary Expanded Edition CD (24-bit) (Columbia/Legacy USA CK 65489) (1)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8) "Santana" on Oct 19, 2004 on Original Recording Remastered Legacy Edition 2CD (remastered) (Columbia/Legacy Europe COL 512912 2) (6)(7) "Viva Santana!" in August 1988 on 3LP (gf) (CBS USA C3X 44344) (CBS Europe 462500 1) (6)(7) "Viva Santana!" on October 4, 1988 on 2CD (CBS USA C2K 44344) (CBS Europe 462500 2) (CBS/Sony Japan 46DP 5334~5) (6)(7) "Viva Santana!" on November 3, 2010 on Limited Edition 3CD (remastered/papersleeve) (Sony Records Int'l Japan SICP 2897~9) (7) "Dance Of The Rainbow Serpent" on August 8, 1995 on 3CD (long box set) (Columbia/Legacy USA C3K 64605) (7) "Dance Of The Rainbow Serpent" in 1995 on 3CD (box set) (Columbia/Legacy USA C3K 65411) (7) "Dance Of The Rainbow Serpent" on December 1, 1995 3CD (box set) (Sony Japan SRCS 7790~2) (7) "Dance Of The Rainbow Serpent" in 1997 3CD (box set) (Columbia/Legacy Europe 489323 2) |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

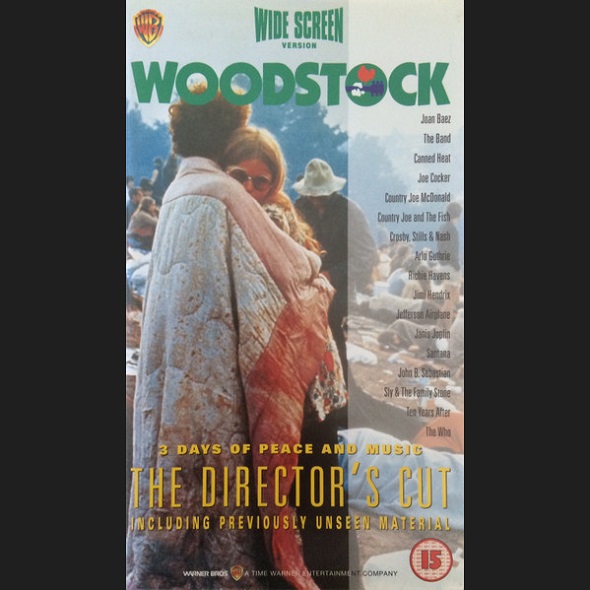

(7) "Woodstock. The Movie" premiere on March 26, 1970 in U.S. movie theaters (7) "Woodstock I & II" in 1980 on Betamax-PAL (Warner Home Video Germany PEXN 1015) (7) "Woodstock I & II" in 1980 on Betamax-SECAM (Warner Home Video France SEV 1015) (7) "Woodstock" in 1989 on 2LD-NTSC (Warner Home Video USA 11762 A/B) (7) "Woodstock" in 1989 on 2LD-NTSC (gf) (Warner Home Video Japan NJL-11762) (7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" in 1994 on 3LD-NTSC (box set) (Warner Home Video USA 13549) (7) "Woodstock" in 1989 on VHS-PAL (Warner Home Video UK PES 11762) (Warner Home Video Germany 11762) (Warner Home Video Netherlands SCV 11762) (7) "Woodstock. The Director's Cut!" in 1994 on 2VHS-NTSC (Warner Bros. Records USA/Canada 13549) (7) "Woodstock. The Director's Cut!" in 1994 on 2VHS-PAL (Warner Home Video UK S013549) (Warner Home Video Germany 13600) (7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" on March 25, 1997 on DVD-R1 (Warner Home Video USA 13549) (7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" in 2000 on DVD-R2 (Warner Bros. Records Germany Z5 13549) (Warner Home Video Japan DLT-13549) (7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music" in 2003 on DVD-R2 (Falcon Neue Medien Germany 0241) (7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" in 2008 on DVD-R2 (Living Colour Entertainment Netherlands 1413541) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" in 2009 on 40th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition 4DVD-R1 (copy protected) (Warner Bros. Records USA 2000007993) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" in 2009 on 40th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition Deluxe 3DVD-R1 (box set/numbered) (Warner Bros. Records USA 3000021617/18/19-4000018186) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music" in 2009 on 40th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition 4DVD-R2 (Warner Bros. Records Germany 3000021410) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music" on June 9, 2009 on Amazon Exclusive 40th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition Deluxe 2Blu-ray-A (remastered/numbered) (Warner Bros. Records USA 4000018186) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music" in 2009 on 40th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition 2Blu-ray-B (remastered) (Warner Bros. Records Germany 1000106874) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut!" on September 14, 2014 on Limited Special Edition 2Blu-ray-A (remastered) (Warner Bros. Records Japan WBA-Y2564-A/10005056509) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Days Of Peace & Music. The Director's Cut! 40th Anniversary Revisited" in 2014 on 3Blu-ray-A (remastered) (Warner Bros. Records USA 3000059390) (2)(7) "Woodstock. 3 Jours De Musique Et De Paix. La Version Longue" in 2019 on 2Blu-ray-B (Warner Home Video France 5051889005155) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" on October 18, 1988 on VHS-NTSC (CBS Music Video Enterprises USA 19V-49007) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" in 1988 on VHS-PAL (CBS Music Video Enterprises UK 01-049007-81) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" in 1988 on VHS-SECAM (CBS Music Video Enterprises France 01-049007-83) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" in 1988 on LD-NTSC (CBS Music Video Enterprises Japan 42LP 115) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" in 1989 on LD-NTSC (CBS Music Video Enterprises USA ID6333CB) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" on September 12, 2006 on DVD-R1 (CBS Music Video Enterprises USA 82876 89534 9) (7) "Viva Santana! An Intimate Conversation With Carlos Santana" in 2006 on DVD-R2 (CBS Music Video Enterprises Europe 88697355669) (7) "Viva Santana!" on March 25, 2009 on 2CD + DVD-R2 (Sony Japan SICP 2192-4) |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Photos by Victor Englebert (www.victorenglebert.com July 10, 2009): Back in 1969, I was showing my photographic portfolio to Business Week’s photo editor when he said, “Would you like to photograph a rock concert? It will take place tomorrow in Bethel, New York.” I had never photographed rock concerts. I didn’t even have a clear idea of what a rock concert was. I photographed mostly wild people in wild environments, from deserts to rain forests, for such magazines as National Geographic. But I never turned down an assignment. I did the right thing, for at Woodstock I would photograph wild people too. Thanks to my photographs there are things that I remember more clearly. Santana’s band, for example, though not the many other musicians, as I focused my attention on the mind-boggling crowd. The hundreds of thousands of young men and women whose faces radiated sometimes as if they had just seen Jesus Christ himself. The stoned naked man who hung high on a music tower to better expose himself. The sleepers packed like sardines at night. The restless men who kicked the sleepers’ shoes away from them as they walked around. And then, in the morning after a night’s rain, the kids who kept sleeping as if this could save them from dealing with the mud baths into which they had been slowly sinking (hundreds abandoned their blankets and sleeping bags stuck under the mud). And the many who at the end were forced to walk back shoeless to their cars. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by Bill Eppridge James Estrin (The New York Times July 30, 2009): Bill Eppridge, who photographed the Woodstock Music and Art Fair 40 years ago, remembers it as a beautiful coda to a painful decade. “For me, it was a visual feast, a never-ending succession of moments that is impossible to forget,” he says. Mr. Eppridge, now 71 and renowned as a teacher and mentor, joined Life magazine as a staff photographer in the early ’60s and stayed until the magazine folded in 1972. He covered many of the most important stories of the time, including the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign. It was Mr. Eppridge who made the iconic image of a stunned busboy holding the senator moments after he was shot. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by Jason Lauré Threading his way back and forth from the stage, through a sea of happy audience members, Jason Lauré photographed the communal life that was an essential part of the phenomenon that was Woodstock. Never intrusive, yet working close-up, he managed to capture these innocent moments in the pond and in the woods with the same compassion and intimacy he brought to his coverage of all the crucial events of the era. After Woodstock, he photographed such legends as Jimi Hendrix, Tina Turner, and Jim Morrison of the Doors. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by David Marks David Marks is a South African musician and archivist who was at Woodstock helping Bill Hanley with the sound. Judi Davis (South Coast Herald August 18, 2017): South Coast professional musician, songwriter and sound engineer, David Marks of 3rd Ear Music, will have had good reasons to feel nostalgic this week. It was 48 years ago today that the last notes rang out at the music festival, remembered simply as Woodstock, that defined a generation – and David was there, right in the thick of it, as a member of the Woodstock sound crew. |

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by Jim Marshall Michelle Margetts (Literary Hub August 15, 2019): Jim Marshall’s outpouring of work from the original Woodstock festival was prodigious. His images capture what it was like to be there from all perspectives—onstage, offstage, behind the scenes. He was reportedly a dervish of nonstop shooting until he collapsed in a heap backstage sometime during day three. On assignment for Newsweek, Jim seemed to bring an extra focus to capturing the energy of the crowd, including his incredibly striking shot of the technicolor masses. Jim said he had to climb up one of the huge lighting scaffolds bracketing the stage to get this bird’s-eye view, taken with a wide angle “fish-eye” lens. This shot was used as the centerpiece of the live three-album set Woodstock: The Original Soundtrack and More, released in 1970. Jim was a bit afraid of heights, but he had been dosed with acid by the Grateful Dead earlier in the day, and that was the only way he had the guts to climb up on the stanchion and get this now world-famous shot. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by Tucker Ransom |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by Baron Wolman Angie Martoccio (Rolling Stone August 12, 2019): As Rolling Stone‘s first chief photographer, Wolman heavily documented the festival, witnessing legendary musical moments like Santana’s psychedelic “Soul Sacrifice” and Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick belting “Somebody to Love” in her iconic silk-fringed dress. Wolman’s main focus, however, was the heart of the festival: the attendees. Whether they were camping out in tents or bathing in the nude with their children in tow, Wolman captured the essence of what it felt like to really be there. “It was a perfect storm,” Wolman tells Rolling Stone from his home in Santa Fe. “Fifty years later, people are still talking about Woodstock and the meaning of it. Clearly it was and still is an important event to show how far we’ve gotten away from the the peace, love, and music of Woodstock. Fifty years later, what other event do you think about? The bombing of Pearl Harbor. The Berlin Wall going up and down. And Woodstock.” What was the best act you witnessed? Santana, far and away. And not only because the pictures I took of him, but because of his story about being totally stoned going on stage. You know that story…he and Jerry Garcia. He said his guitar felt like a steel snake in his hand, he had no idea what he was playing. He looked out at the audience and he said, “All I saw were eyes and teeth.” But that set..It’s become mystical and identified with Woodstock, for sure. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos by Various Authors |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Uncredited Photos |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Photos from the Crowd |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

|